Home » Who We Are » Our story

A Millennia-Old Bond with Our Land

The earliest evidence of Slavic communities in the region now home to Slovenes in Italy dates back to the 6th to 8th centuries AD. Historian Paul the Deacon recorded the settlement of these populations along the Natisone River in the 7th century AD, while their presence in the Istrian hinterland is noted in the Placitum of Riziano from 804 AD.

For centuries, Slovenes lacked their own nation-state, and their lands were governed by various political powers. The areas now inhabited by Slovenes in Italy have undergone unique historical developments, which continue to shape the diverse realities of the Slovene national community today.

From a Common Empire to Nation-States

During the First World War, Slovenes—except those from the province of Udine—fought for the Austro-Hungarian Empire along the Isonzo and other fronts. After the war, Gorizia, the province of Trieste, and the Val Canale, along with the regions of Primorska and Notranjska (now in Slovenia), came under Italian control. In the decade that followed, around one hundred thousand people emigrated from these areas to Yugoslavia or overseas.

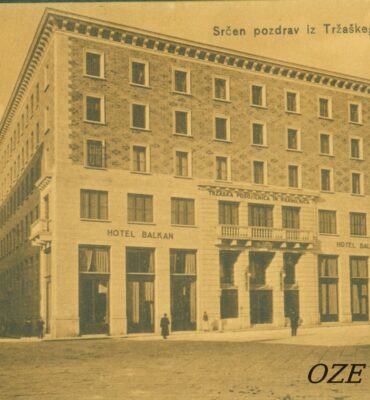

In the early 20th century, the Slovene community was particularly vibrant and active. A prominent symbol of this vitality in Trieste was the Narodni dom, a true multifunctional centre, which was set on fire by Fascists on 13 July 1920. Other important cultural institutions, such as the Trgovski dom in Gorizia and the Narodni dom in San Giovanni in Trieste, met similar fates.

A Dark Period That Lasted Twenty-Five Years

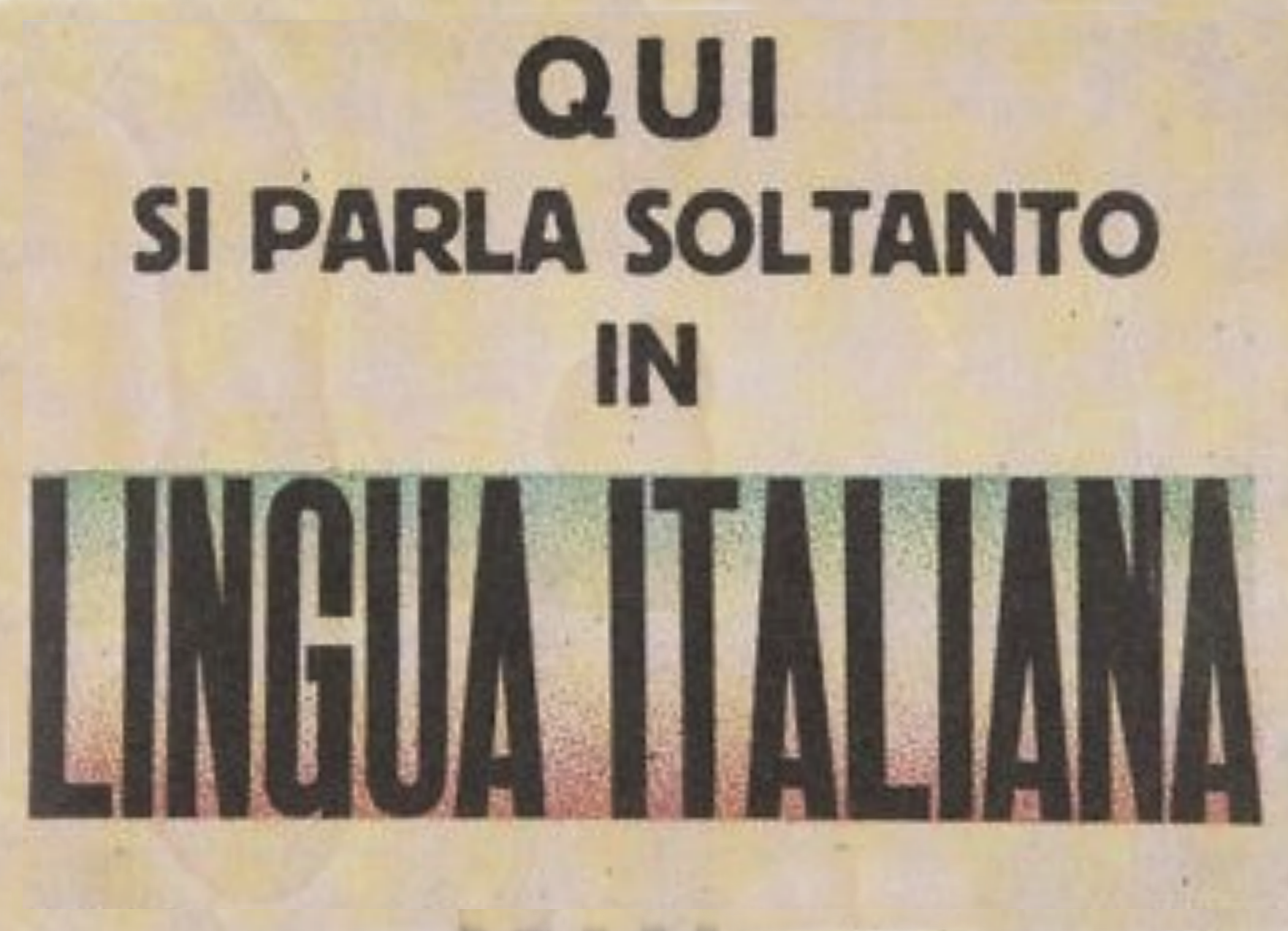

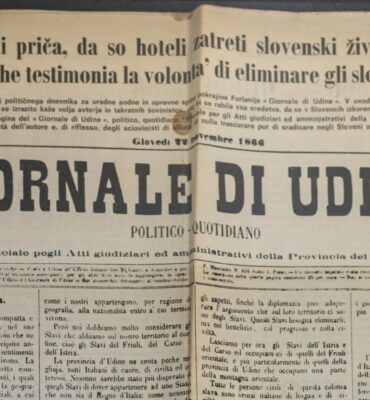

During the Fascist era, Slovenes were viewed by the Italian state as foreign citizens who needed to be eliminated as quickly as possible. A policy of forced Italianisation was implemented, which included prioritising Italians for public sector jobs, abolishing the teaching of the Slovene language in schools from 1927, and Italianising Slovene surnames. Speaking Slovene in public was forbidden, Slovene-language publishing activities were suppressed, and nearly all cultural institutions were closed down.

The oppression and violence they faced fuelled resistance and discontent among the Slovenes. With the outbreak of the Second World War, many joined the National Liberation Front, finding support from the Allies, with whom they eventually defeated the Nazi-Fascist forces.

After the war, the linguistic and cultural situation for Slovenes in Italy began to normalise, with Slovene gaining recognition in institutional and public spheres. In the following decades, the community progressively advocated for and achieved greater protection for minority rights.

A New Country, New International Relationships

On 25 June 1991, Slovenia declared its independence. Following this event, relations between Slovenia and Italy gradually improved, also supported by the transformation of the political and ideological landscape after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

In December 2007, Slovenia’s entry into the Schengen Area effectively removed the physical borders between Slovenia and Italy. These developments have contributed to enhancing the status and prestige of Slovenia and the Slovene language, while simultaneously boosting the self-esteem of the Slovene national community residing in Italy.

Da vicino

Il Narodni dom – e le altre Case del popolo

La Benecia e il difficile periodo del XX secolo

Piazza Transalpina: la piazza di due città

I confini si spostano, le persone restano